The Northern Latitudes have always been a challenging destination to sail but worth it. When I had the offer of taking over a boat as relief captain in the North of Norway for two months, I replied YES without a moment’s doubt. To be honest, I had no idea what I was signing up for, but there I was in December 2018 looking at google maps to see where I would be joining the vessel.

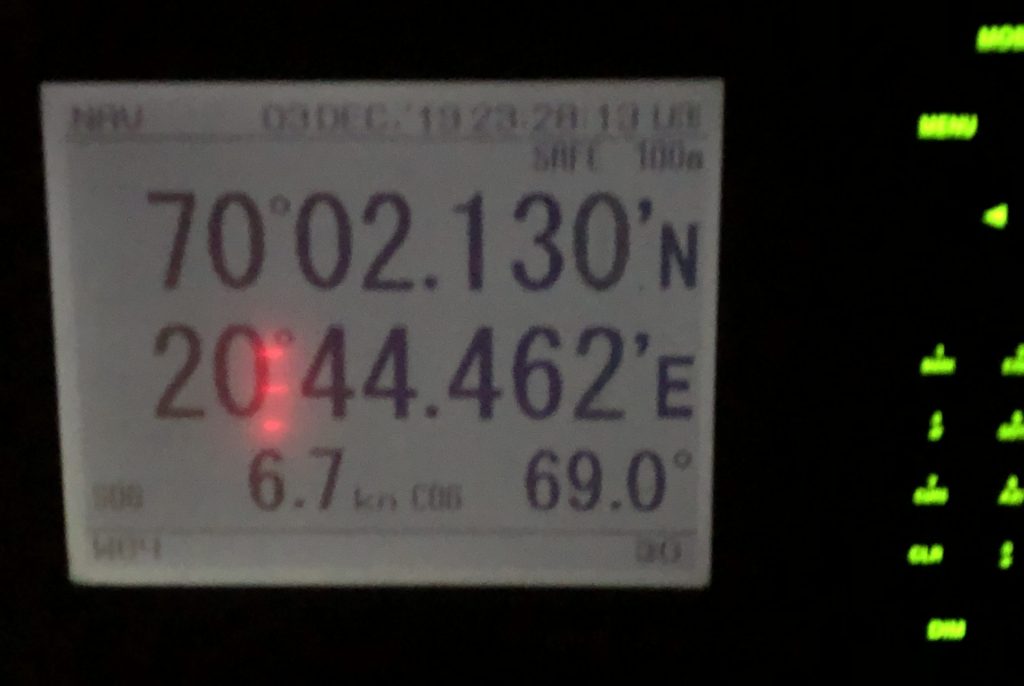

The vessel, a nearly 100-year-old lady, was originally built in 1924 in The Netherlands as a fishing lugger with no propulsion other than sails. She had had many lives before Oceanwide Expeditions rebuild her in 1984 as a three-masted expedition schooner. In December 2018 SV Rembrandt van Rijn was a sailing passenger vessel (call sign YJRJ3), she had a length over spars of 56 metres, 308 GT, and was equipped with two Cummings engines for destinations in remote areas such as Iceland, Norway, Spitsbergen and Greenland. The vessel was run by nine to ten crew, two expedition staff, and carried up to twenty-six guests. As the company was an expedition vessel operator, she had been treated the same way as the larger vessels in the fleet and had been fully equipped with modern navigational aids. In addition to ECDIS and a forward-looking sonar, what was new to me was the infrared FLIR camera that enabled you to see at night.

I decided to reach Tromsø two days before embarking to acclimatise and buy gear best bought in Norway, as I was unsure if the Mallorca Decathlon could gear me up accordingly. To have those two days to see the surroundings was a blessing, dog sledging, visiting the Roald Amundsen Museum, and generally getting into the Arctic atmosphere … wonderful!

North Spitsbergen, ArcticSpring, May, Rembrandt van Rijn © Katja Riedel – Oceanwide Expeditions

In the North of Norway, during January, there are twenty hours of night-time.

It seemed a little strange to me at first, as my body stepped into evening mode as the sun went down, and I realised that instead of going to bed, it was only 3 pm. However, I became used to the rhythm in a matter of days. It is the opposite, of course, in summer, where there are twenty-four hours of sunlight, but that is worthy of its own story.

I have been observing and following whales for a fair part of my life, as I have been involved in whale-watching and research expeditions and have sailed the oceans for twenty-four years.

The two main species that we were looking for here in the winter were humpback whales and killer whales. Both of them came to the Northern fjords to feed on herring, who arrived at these areas of Western Norway’s coast in huge schools. The herring presence in these fjords fluctuated, a tremendous invasion was observed in 2011 and 2012, for example, but few herring were seen in 2017.

It is uncertain, but it seems that 400-600 humpbacks visit these fjords during the season, with some individuals remaining in the area for a period of four to six weeks. These humpbacks consume an estimated 20,000 to 25,000 tonnes of herring within the season, about half of what the local fisheries catch.

Looking for herring was not my job, and I wouldn’t have known where to start, but my eyes were trained to look for blows on the horizon. With only four hours of light in the peak of winter, one needed to leave port or anchorage well before the sunlight hit the fjords, which is when navigational aids became crucial. It was such a pleasure to work with top range radars, ECDIS, night vision and all the bridge equipment available to make our way through the fjords to where the whales had last been seen. The night vision was the gamechanger, as you could observe the blows at night due to the temperature difference.

This generally allowed us to arrive at the whales by sunrise. If that was not the case, as soon as the sun started to rise, the bridge asked for the assistance of an expedition guide and a deckhand, to help with the search by climbing up the bridge with their binoculars looking for blows. The moment a blow was seen, the message was relayed to the guests that it was time to wrap up the breakfast. I must admit that I had never seen so many humpback whales in my life, they really were there in large numbers, and the sightings were spectacular.

Without a doubt, the orcas were the highlight for me personally, as I had been passionate about them for many years. They were less easy to spot, moved faster and also changed course underwater more regularly than humpbacks. We encountered groups of females, mother and calf sightings or solitary males steaming their way through the fjords.

Since the massive presence of herring occurred in these North of Norway fjords, there had been a boom in the whale watch industry. We had the advantage of being first on the spot, as our vessel allowed us to travel “overnight”, but once the light hit the fjords, small ribs appeared out of nowhere. I must say that generally, the Norwegians were respectful towards the whales and the other vessels, which was a crucial element when observing whales, compared to previous whale-watching experiences I had had in Spain, Ecuador or Brazil. There was always ‘one’ that squeezed in where we all knew they shouldn’t, to cash-in on the well-paid customer experience at any cost.

During my command, a new local regulation was enforced where no whale-watching vessel could come closer than 0,2 Nm from any fishing vessel, and 0,4Nm between anyone swimming, paddling or diving and the nearest fishing vessel.

Yes swimming! It had become more and more popular for the brave or reckless to jump in the water to see the humpback or killer whales in their element. I did not see any problem with that, as I would love to do the same myself one day, but if a Japanese tourist became caught in the net of the herringer… maybe not. For me, to swim, dive or paddle away from the fishing activities made sense for safety and created a genuine two-sided encounter, which was ‘the experience’ that appealed to me most.

Those twenty hours of darkness were the opportunity that many guests had been waiting for to observe the aurora borealis. The expedition staff programmed different hikes to explore nature during their stay. Equipped with radios, medical kit, snowshoes, SAT phones, headlamps, etc., off they went up the mountain in search of wildlife and the aurora borealis. I had to wait several days before my first sighting from the ship as the light from the shore or the deck obstructed the sightings. You will be surprised to know that you can actually see them from the photo on your mobile phone before your eyes view them. They started very subtly and were not visible every day. When you were lucky enough to see these big greenish substances covering the skies, it was quite overwhelming. They moved slowly, a little like clouds and then appeared to be different as the tones and brightness changed. I could not follow all the expedition staff’s talks but basically understood that they were a type of dust coming from the galaxy that created a chemical reaction once in contact with the earth’s atmosphere.

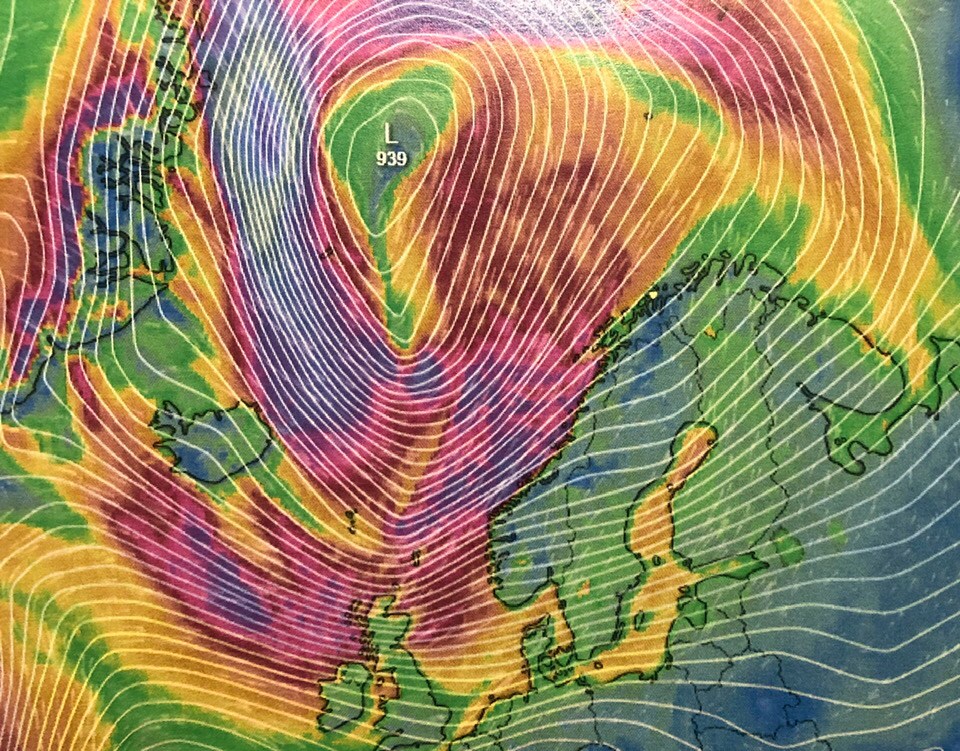

The weather was generally mild with little wind, but when it blew, it blew.

I had the pleasure of working with two very professional ladies running the bridge in three watches. When any bad prediction arose, all officers took part in monitoring and planning places to hide. It only happened once, but I remember it well as I had never seen a low of 939 millibars on a forecast before. You could sail deep into the fjords for shelter and look for some fishing pier that allowed you to stay for several nights. Most passengers understood that weather was a ‘force majeure’ and is part of sailing in the arctic in winter. This was when you appreciated the pleasure of working with experienced and professional crew, which for me was something I was enjoying more and more; expedition staff organised extra lectures and hikes, the galley team prepared good food for the guests, the crew prepared extra lines and did all the work that needed to be done to keep the vessel safe.

As much as I had sailed larger vessels with many more crew, I must admit that I learned one important manoeuvre whilst in the port of Tromsø. One evening, with no wind at all, the rattling sound of the anchor woke me, and I saw one of the larger Norwegian Ro-Ro vessels coming into port. I went out on the bridge to see what was happening, and the vessel had dropped anchor two hundred metres away from the pier whilst coming in alongside. I had no idea why, and my first though was that maybe they were facing some technical issues. It was only a week later that I understood that they had dropped the anchor just in case the wind picked-up, to be able to sail off should the wind push them onto the peer. I practised the manoeuvre with my crew and proudly added the Norwegian way of going alongside in unstable weather to my bag of tricks.

To finish, I can highly recommend the North of Norway in winter as a destination for well-prepared and equipped vessels. As captain, to work with the Norwegian authorities, providers and agents is a very relaxed and professional experience. The overall experience of seeing whales and orcas in fjords covered in snow is absolutely picturesque, and without a doubt, an aurora sighting is the cherry on the cake.

As much as I looked over my shoulder once in a while, I must admit I did not see any trolls called Ymer, Dovregubben, or Hrungnir, nor did I see Thor running around with a hammer but let me know if you get lucky.

Capt. Dominique Geysen

Heading Photo: North Norway, Aurora Borealis © Jurriaan Hodzelmans – Oceanwide Expeditions